The congregation at Temple Beth Or taught me many things. I learned to read Hebrew. I learned the history of the Jewish people and their historic struggles with many kinds of strife. I learned how hard work and compassion for others could reward you with far more than wages at a job. I learned that not all the people in my temple were perfect, but each had a purpose and a place. I learned to be a leader of the congregation and of weekly Shabbat services. I learned how to make as much noise as possible when I heard the name HAMAN! But what I never learned was how to end it all. How could it be that I, the president of the congregation, was going to be the one to make the decision that it was time to close the doors? How, after only 60 years, did this happen? How can I go over to our cemetery and look at the headstones of all these great people who had built so much out of so little? What did I do, or not do, that could have averted this awful end?

What do you do with the memorabilia that documents the history of your congregation? How about the Torahs, the religious school books, the Haggadot, the memorial boards, the eternal light, the building itself? These were all questions without answers.

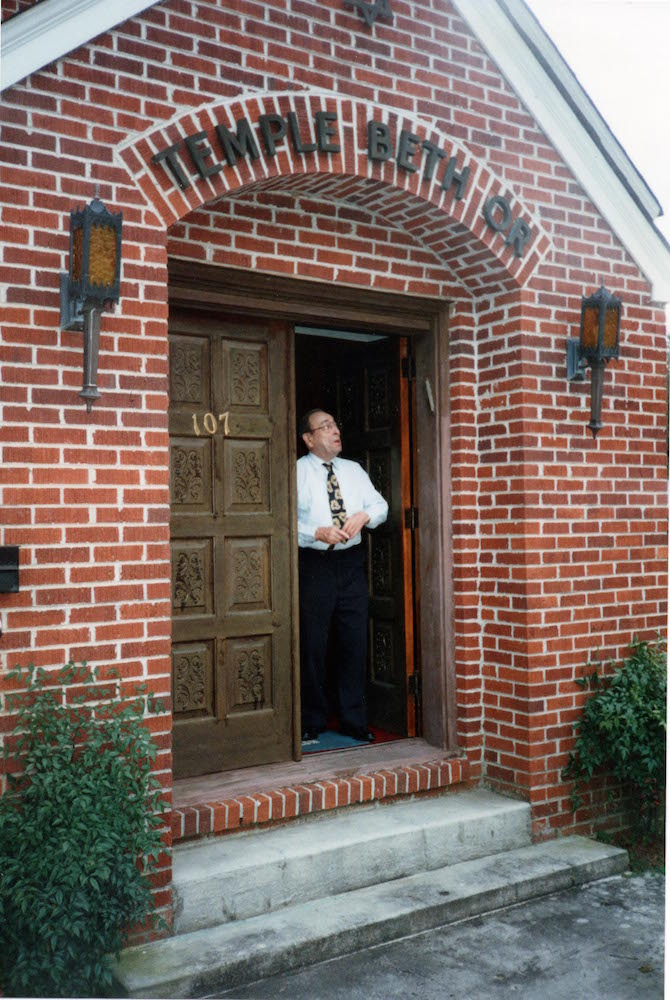

Temple Beth Or was founded in April 1945 as a Conservative congregation by Jewish families that lived in small towns in the Pee Dee region of South Carolina. They met in members’ homes until they finally decided upon a location for a synagogue in Kingstree. On April 10, 1949, the cornerstone for Temple Beth Or was placed. Like all congregations, there were Shabbat services, onegs, seders, Purim festivals, men’s club and Sisterhood, religious school, Hanukkah parties, field trips, youth group, monthly bulletins, and fundraisers. We did it all. Except we didn’t have a rabbi. How could we? We were only a small group of families in a small town.

Fortunately, Synagogue Emanu-El in Charleston was willing to take us under its wing for many years; with its help every child in our congregation for decades was either a bar or bat mitzvah. Every year, for the High Holidays, we hosted a rabbinical student from the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York to lead us in prayer. Our congregation prospered. Little did we know that our level of education, drive, and success would contribute to our demise. It wasn’t long before our children, who had achieved excellence in the classroom and society, were now leaving our sleepy rural setting for life in bustling cities around the country. The job market was changing and our community wasn’t. The proprietors of the many Jewish businesses in Kingstree and nearby towns were retiring and closing their businesses.

As our numbers diminished, so did our potential to attract new members. How do you convince that new Jewish couple with the four-year-old daughter to come to your temple when holding Shabbat services depends on finding a minyan; when you have no religious school because there are only two children in the congregation; when all of that and more is offered at another temple 40 miles away?

I suspect similar scenarios have taken place in other small Jewish communities in South Carolina, such as Camden, Dillon, and Orangeburg—isolated towns negatively affected by changes in the local economy and population. Some small congregations, like Temple Beth Elohim in Georgetown, have been able to avoid extinction because of their geographical advantage. Retirees moving south help to sustain these congregations, though it’s a different environment, where religious school is taught by 70-year-olds to 70-year-olds and the only kids who are “members” are grandchildren who are visiting. The congregations dominated by older members are viable and dynamic, but to survive they must be located in an area with institutions and organizations that are vital to a thriving city or town. Many of our small communities in South Carolina don’t have the societal infrastructure needed to retain their residents, let alone draw newcomers.

I only hope you don’t have to be the person who turns out the light.