Leon Banov’s history as an immigrant who served as Charleston’s health director for about 40 years is well known to 20th-century residents of the South Carolina city. In 1895, at the age of seven, he left a village in Russia’s Suwalki Gubernia and came to Charleston; he became a pharmacist at age 19; and he graduated from the Medical College of South Carolina in 1917 at age 28. He served in the Charleston City Health Department as assistant chief bacteriologist in 1912 and as chief food inspector in 1917–1920; he was selected director of the new Charleston County health department in 1920; and in 1926, the county named him director of the combined city-county health department. He retired as health director in 1962, after 50 years of promoting public health in Charleston County.1

On this journey Dr. Banov also taught pharmaceutical Latin, arithmetic, and commercial pharmacy at the Medical College’s School of Pharmacy between 1913 and 1917, and he taught public health and preventive medicine at the Medical College, rising from assistant professor to associate professor to professor, and ultimately professor emeritus.

On this journey Dr. Banov also taught pharmaceutical Latin, arithmetic, and commercial pharmacy at the Medical College’s School of Pharmacy between 1913 and 1917, and he taught public health and preventive medicine at the Medical College, rising from assistant professor to associate professor to professor, and ultimately professor emeritus.

What is less known is that Leon Banov was a Renaissance man. He painted. A 1961 article in the News and Courier quoted him as saying, “I paint myself. I’m the cheapest model I’ve got!” He sculpted. He photographed and developed his own film in an addition—known to the family as “the little house”—built next to his Byrnes Downs residence. He constructed Rube Goldberg contraptions in his house, the little house, and the health department. These ranged from an examination table that folded into the wall, to an apparatus that extinguished lights at a fixed time with the aid of a mouse trap and an alarm clock! He used his carpentry skills to make cabinets, desks, closet enhancements, and other things for the house he shared with his wife, Minnie. He wrote not just medical articles, but also a semi-autobiographical book, As I Recall: the Story of the Charleston County Health Department (R.L. Bryan, 1970). He portrayed Tevye in a local production of Fiddler on the Roof.

In the 1950s, he broadcast a program, Your Health, on WCSC and WTMA radio stations. From 1953 through 1956, in the early days of black and white television in Charleston, he developed and ran a weekly program on WCSC-TV called You and Your Health, giving advice to Lowcountry viewers on everything from the way to place pots on the stove (put the handles to the side) to pointers on keeping fit. The show followed Howdy Doody on Saturdays and Farm and Home Hour on other days. His signature greeting was, “Good afternoon and good health to you.” (The “you” came out as a Charleston “ya.” The man who spoke no English when he arrived in the USA had developed a Charleston accent!) He not only produced the show; he was its only star! (Once or twice, when I was probably a pre-teen, my grandfather put me to work assisting him behind the scenes, moving text around on a black felt background behind him.) There were no rehearsals and no videotaping—Banov had only one “take” to get it right.

My grandfather also invented things. In about 1920, he and Dr. George McFarlane Mood (1880–1957), professor of bacteriology and hygiene at the Medical College and city bacteriologist, developed Clar-O-Type, a solution to clean typewriter keys. Applied with a dauber, Clar-O-Type cleaned keys clogged from the ink in typewriter ribbons. Sold in a distinctive blue cobalt bottle, the solution came with a little piece of felt to dry the keys after the liquid was applied.

A Trademark Application for CLAROTYPE was filed in the United States Patent Office on November 24, 1919, and given a Serial Number of 125,219. A Trademark Registration was awarded on August 10, 1920, and granted Registration No. 133,935. An old book indicates that the company obtained a patent on the solution, Patent No. 5730, on September 6, 1921, but it is not clear that the U.S. Patent Office actually issued a patent for the invention.

On April 21, 1921, the S.C. Secretary of State issued a charter to the Clarotype Company of Charleston, which was capitalized at $20,000. Dr. Mood was president and secretary of the company; Dr. Banov was vice-president and treasurer.

Clar-O-Type was produced on an upper floor of an old warehouse on Vendue Range at Prioleau Street, where the Vendue Hotel now stands. To reach the factory you had to pull on the rope of a freight elevator. The principal employees of the factory were African-American women, who mixed the solution, put labels on the bottles, filled the bottles, and boxed the materials. Sometimes during the summer, Leon’s son (my father) Leon Banov, Jr., worked in the factory.

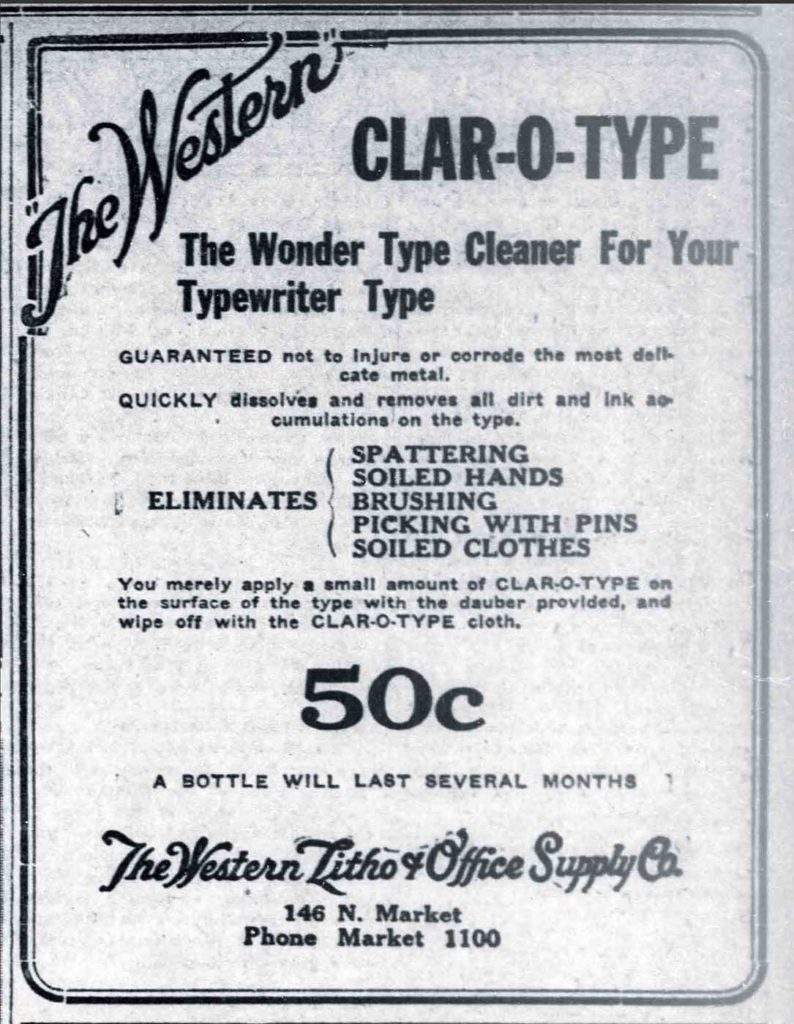

The Clarotype Company advertised in newspapers from coast to coast, from Eugene, Oregon, to Wilmington, Delaware, from Boston, Massachusetts, to Pawhuska, Oklahoma, and in many small newspapers. Ads claimed it was a “Wonder Type Cleaner.” One such ad in the Wichita Eagle touted Clar-O-Type as “The Wonder Type Cleaner for your Typewriter Type” and stated it

(SPATTERING

(SOILED HANDS

ELIMINATES (BRUSHING

(PICKING WITH PINS

(SOILED CLOTHES

The advertised price was 50 cents, and a bottle was said to “last several months.” Fifty cents was a standard price for many years, though sometimes stores sold it at a discount, from 27 cents (by a store going out of business) to 43 cents. In the early 1970s, some stores sold it for 79 cents and as high as one dollar.

In February 1920, the company placed an introductory ad for the product in a trade journal, touting:

Clarotype dissolves all dirt and ink accumulations in the type and is guaranteed not to corrode or injure the metal. An extremely small amount of the liquid is necessary for cleaning purposes and because it is sold at the extremely moderate price of 50c per container, it carries a particular appeal to the average dealer who will find it a very essential typewriter accessory.

The product was carried not only by stationery stores across the country, but also by R. H. Macy & Company in New York.

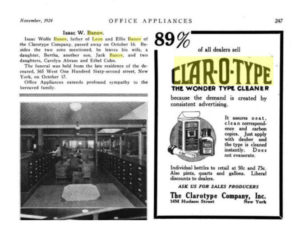

While the cleaning solution was manufactured in Charleston, the headquarters was in New York City, under the auspices of Messers. Leon and Ellis Banov, sons of Wolf Banov,2 my grandfather’s cousin. Leon (1890–1978) and Ellis (1895–1979) were salesmen for Art Steel Company, an office supply business in New York City. Occasionally, particularly in the early years of Clar-O-Type, the company placed help-wanted ads for “young lady” demonstrators to show off “Clar-o-Type, the wonder type cleaner” to stenographers and office workers.

My grandfather invented two other, lesser-known, products. One was “Cant-Slip,” a solution which “thoroughly cleans the [typewriter] roller and gives it a new gripping surface.” The United States Patent Office Gazette of June 2, 1942, stated that Clarotype Company, Inc., filed a patent for Cant-Slip on February 4, 1942, and that it was given Patent 395,709. The journal stated that the company claimed use of the product since August 14, 1919. Cant Slip was not advertised nearly as much as Clar-O-Type, and the product seems to have slipped into oblivion after a while.

My grandfather invented two other, lesser-known, products. One was “Cant-Slip,” a solution which “thoroughly cleans the [typewriter] roller and gives it a new gripping surface.” The United States Patent Office Gazette of June 2, 1942, stated that Clarotype Company, Inc., filed a patent for Cant-Slip on February 4, 1942, and that it was given Patent 395,709. The journal stated that the company claimed use of the product since August 14, 1919. Cant Slip was not advertised nearly as much as Clar-O-Type, and the product seems to have slipped into oblivion after a while.

Another of my grandfather’s inventions was “Flipit,” a finger moistener for bank tellers and others handling money and paper. I believe he developed it in the 1960s. It came in a little plastic case. Clarotype stopped making it in the 1970s.

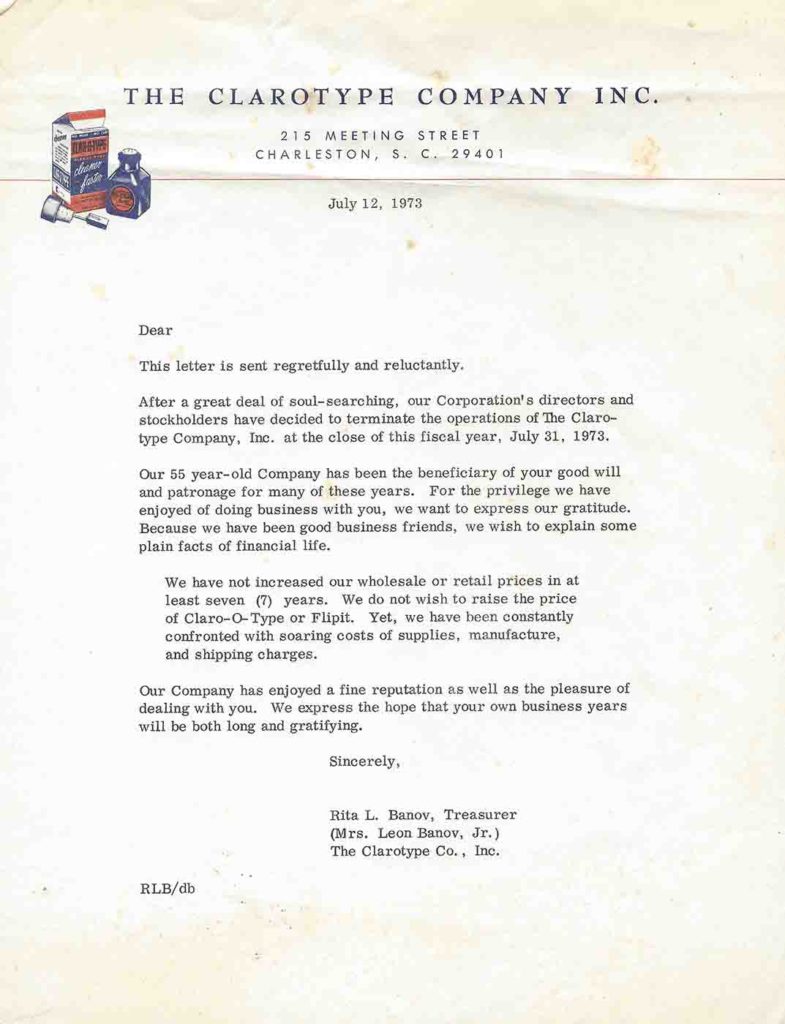

My mother, Rita Landesman Banov, was secretary of the Clarotype Company in the 1960s and ’70s and became president after my grandfather died in 1971. During this period the company contracted with Jack Kahn of Charleston (1920-2007) to manufacture Clar-O-Type. By the 1970s, electronic word processors were replacing manual typewriters, thus making Clar-O-Type obsolete. In July 1972, the company ceased manufacturing Clar-O-Type, and in 1975, after trying to sell the business without success, Rita dissolved the firm.

In 1979, she wrote an article in the Charleston Evening Post about the Clarotype Company, which described its operation:

Over the years, that little cottage industry provided typists with a good office aid and several of Charleston’s black families with a good income. When one family member was ill and unable to work, another took his place. Each regarded it his business, training a succeeding generation to fill bottles, paste labels, position a dauber felt and cork atop a wire, and box dozens and grosses of the finished product. All kinds of Rube Goldberg contraptions figured in the process, long carried out in the building at the corner of Venue Range and Gendron Street.

My mother went on to bemoan the fact that it was very hard for the Clarotype Company to survive by essentially making a single product. “Now, if anyone has an old familiar cobalt blue Clarotype bottle stashed away anywhere,” she continued, “you’ve got the makings of an antique. If you haven’t, please don’t call me. We used up every bottle and then quietly faded away into local history in 1975.” In 2021, the only way to buy a Clar-O-Type bottle is to pay eBay from $10 to $18 for it! My family and I kept a few bottles for posterity.

1 For more on Leon Banov’s public health career, specifically, his role in combating the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918, see the fall 2020 issue of the Jewish Historical Society of South Carolina magazine: https://jhssc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/JHSSC-Fall-2020-Magazine-website-1.pdf

2 For more on Wolf Banov, see my article “Banov & Volaski” at https://merchants.jhssc.org/merchant-stories/

All images courtesy of Alan Banov.