Henry and Paula Kornblum Popowski with their son Mark in Landshut, Germany, 1949. Special Collections, College of Charleston.

Their stories of survival differed dramatically. My father lived as a young man in Warsaw in the late 1930s. When Germany invaded Poland he was conscripted into the Polish army. After Poland surrendered, he found his way back to Kaluszyn to warn his family of the impending danger and urge them to leave. Two of his six siblings hid in the woods and the remainder of the Popowski family perished. My father sought refuge in the Warsaw ghetto and subsequently was incarcerated in the following concentration camps: Kraśnik, Plaszow, and Ebensee, a sub-camp of Mauthausen. He survived because of his skills as a carpenter, his family’s trade. When he was liberated by the U.S. Army in May 1945, he and several friends attached themselves to a MASH unit and ultimately reached Landshut, Germany, where a displaced persons community evolved.

My mother escaped from Kaluszyn to a labor camp four miles away. Her father, Moshe Kornblum, had buried a number of gold coins in the yard. My mother’s family owned the largest enterprise in Kaluszyn, a flour mill, so she began her journey with the remaining assets of that business. My mother and her sister, Hannah, sewed the coins into their coats and dresses and used them for food, rent, and bribery. (A family friend, the late and beloved South Carolina author Pat Conroy, memorialized the story in the character “the Lady with the Coins” in his novel Beach Music.)

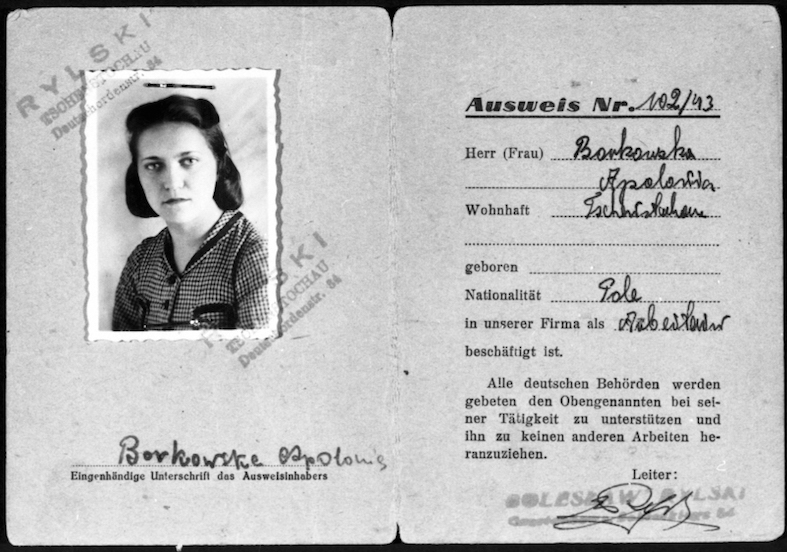

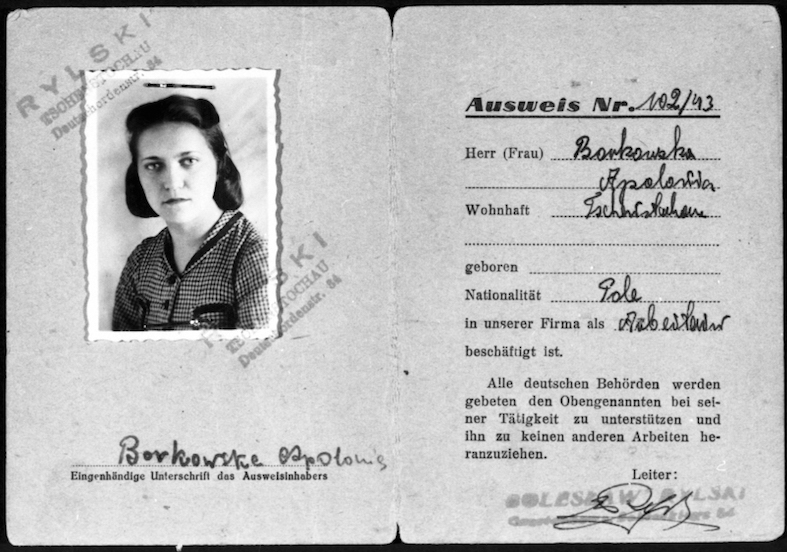

Hannah, with the help of Stanislaw Wozniak, a Catholic work associate of my grandfather, came to the labor camp and facilitated my mother’s escape. My mother and aunt, with Mr. Wozniak’s assistance, made their way to Warsaw where they acquired false identification papers, posing as Catholics.

They migrated to Częstochowa, nearly 200 miles from Kaluszyn. There they lived in a convent and worked in a glass factory, using their Catholic identities. After they were liberated in January 1945 by the Russian army, they made their way back to Kaluszyn. My grandparents, my mother’s brother, and numerous family members were gone. The flour mill had been seized.

My mother and aunt found a group of family friends who had survived and together they traveled to Landshut, Germany, where my parents met. They remained there until 1949, waiting for approval to immigrate to America. During that time, they married and the first of their four children, my brother Mark, was born.

My parents’ immigration to Charleston was sponsored by cousins Joseph and Rachel Zucker. Charleston had a uniquely large number of ex-patriot Kalushiners dating back to the late 19th century. Thus, the city was a welcoming place for my parents to begin their new lives—indeed, they were the last Kalushiners to make Charleston their home. I was born in Charleston, followed by my two sisters, Sarah and Martha.

During our childhood, my parents did not discuss the specifics of their war experiences. I would tell my friends that my parents had accents because they were from Europe, my grandparents were killed in the war, and the few family members I had lived in Brooklyn and Israel. As we began our college years, my parents opened up—my mother more than my father. As a survivor of the Warsaw ghetto and the camps my father had seen the Holocaust in all of its horror.

Fast forward, I graduated from college and law school and returned to Charleston to practice law, start a family, and be near my parents. One day in 1994, I was working in my office when Pincus Kolender called. Like my parents, Pincus was a Holocaust survivor and he had known me, literally, from the day I was born. He and fellow Auschwitz survivor Joe Engel wanted Charleston to have a Holocaust memorial. He said Jerry and Anita Goldberg Zucker (Jerry was the grand-nephew of my parents’ sponsors, Joseph and Rachel Zucker) had pledged $60,000 in seed money and local architect Jeffrey Rosenblum had offered to help. Anita is the daughter of survivors Rose Mibab and Carl Goldberg of Jacksonville, Florida, and Jerry’s father Leon Zucker lost the vast majority of his family in the Holocaust. Also, Pincus and Joe had met with Mayor Joe Riley and he pledged his full support. Pincus asked me to chair the project and added that they felt it was so important, they were willing to pay me my hourly rate to do so. They anticipated the cost of the memorial would be $200,000. I told Pincus to give me a night to think about it. Guessing the project would take a year and an hour or so a week of my time, I agreed and told Pincus that paying me was out of the question.

Initially, I questioned the necessity of building a Holocaust memorial in Charleston. Would enough people in a small metropolitan area with a relatively modest Jewish population care? As the project evolved and I saw the gratifying response of both the Jewish and non-Jewish communities, my concern abated and my devotion to the mission intensified.

The five-year period of design, fundraising, and construction was time-consuming, at times contentious, and meaningful. A committee of approximately 20 members of the Jewish community, with survivors Joe Engel, Pincus Kolender, Charles Markowitz, and Sam Greene playing key roles, oversaw the project. An executive committee consisting of Jennifer Phillips, Anita Zucker, Jeffrey Rosenblum, and myself handled the daily tasks and issues. Jennifer Phillips was at the center of our work, devoting her energies full-time to the project. Mayor Riley assigned City Parks Director Steven Livingston and head of Cultural Affairs Ellen Dressler Moryl to the committee, and they worked diligently with us.

From a group of 15 applicants, architect Jonathan Levi of Boston and landscape design firm Design Works of Charleston were selected. At the recommendation of Jeffrey Rosenblum and respected contractor and Jewish community leader Raymond Frisch, the committee chose contractors Stier, Kent & Canady to build the memorial. After receiving their cost estimate of approximately $500,000, we began the fundraising effort, led by Anita. Our timing was fortuitous because the economy was robust and we had broad support from the community at large. Contributions came from countless individuals and—owing largely to Anita’s work—from numerous corporations.

The selection of the site was mildly controversial. A few people preferred the old museum property on Rutledge Avenue, but the consensus was that Marion Square, fronting Calhoun Street, was best because of its visibility. There also was some disagreement about the design proposed by the professionals: some critics wanted a more striking structure and others a greater emphasis on Jewish symbols. The committee finally approved the memorial as you see it now. There was no discussion about the irony of it being next to a towering statue of former vice president and slavery advocate John C. Calhoun. Marion Square, by the way, is owned by the Washington Light Infantry and Sumter Guard and is leased to the City of Charleston. Their member and former South Carolina State Senator Robert Scarborough represented those organizations and skillfully handled the collaboration.

We broke ground on July 23, 1997, and on June 6, 1999, five years after the call from Pincus Kolender, we dedicated the memorial at Marion Square before a crowd of 1,500 people. It was a remarkable day that included a performance by the Charleston Symphony Orchestra conducted by David Stahl, generously sponsored by Walter Seinsheimer and Dr. David Russin. When it ended, I told my mother: “Now our mishpacha who perished have had a proper burial.”