Camp Wah-Kon-Dah was part of a summer camp craze in America that was shaped by the “cult of the strenuous life” (an anti-modernist ideology that sought to repair and strengthen American society through contact with the “great outdoors”), social reform movements of the Progressive Era, and “back-to-nature” work projects of the New Deal.1 Gary Zola describes Jewish camping as a “genuine hybrid of organized camping in America.”2 Jewish organizations founded the first summer camps in the early 1900s to serve both as a pastoral refuge for needy Jewish children in the urban Northeast, and as sites of Americanization for children of recent Jewish immigrants. During the 1930s, Jewish summer camps and retreat centers with political agendas sponsored by communist, socialist, Zionist, and Yiddish organizations grew in popularity. The majority of these institutions were located near the large Jewish population centers along the East Coast. A smaller, but important number of Jewish boarding houses, camps, kosher inns, and the summer location of the North Carolina B’nai B’rith Institute, Wildacres, were situated in the southern mountains.3 For the mid-South, Camp Wah-Kon-Dah represented a different model of private Jewish camping guided by religious pluralism rather than a specific political or denominational expression of Judaism.4

Non-denominational, private Jewish camps grew during the prosperous years after World War II and today dominate Jewish camping, North and South.5 From the 1940s to the 1970s, a new grassroots activism reinforced American Jewish communities, including those in the South, through regional summer camps and year-round adult education. As a “cultural island” in an isolated setting separated from home and parents, summer camp was the perfect place for a total immersion in southern-style Judaism.6 The combination of education, food, music, physical activity, spirituality, tradition, and Judaism brought campers back year after year to experience the camp’s temporary, but powerful recurring community.

Promoting Jewish education, community, cultural life, and most important, continuity—raising Jewish children committed to their faith and its long-term survival—was the life work of southern Jewish camp directors, such as the Popkin brothers at Camp Blue Star in Hendersonville, North Carolina (1948), and Macy Hart at Camp Henry S. Jacobs in Utica, Mississippi (1970), a project affiliated with the Reform Movement in Judaism. During a regional fundraising campaign to secure property for Camp Jacobs in the 1960s, the project was touted as “The Key to a Living Judaism” and promised to send forth “young Jews proud of their faith and heritage, ready to go to college as committed Jewish Youth.”7

The concept of a vital “living” Judaism remains at the philosophical core of southern Jewish camps today. Camp Blue Star’s contemporary “Living Judaism” program “integrates Jewish values, culture, and traditions” that “teach as well as uplift.”8 Southern Jewish denominational camps with similar educational missions include Camp Judaea in Hendersonville, North Carolina (1960), a program of Hadassah, the Women’s Zionist Organization of America, and Camp Ramah Darom (Ramah of the South) in north Georgia (1997), affiliated with the Conservative Movement in Judaism.9 Ramah’s Center for Southern Jewry provides adult and family programs throughout the year for local Jewish families. Camp Darom in Wildersville, Tennessee, is a modern Orthodox Zionist camp supported by Baron Hirsch Congregation in Memphis, and described as “the only Orthodox sleep away camp in the entire south.”10

Camp Blue Star, the “oldest, family-owned, private, kosher Jewish camp in the southern United States,” was founded in 1948 on 740 acres in the western mountains of North Carolina, the same year as the founding of the state of Israel.11 Jonathan Sarna describes this era as a “crucial decade in Jewish camping,” in which Jewish education was both an expression of “cultural resistance” after the Holocaust and an American promise to build and uphold the Jewish people.12 Brothers Herman, Harry, and Ben Popkin were leaders in Atlanta-based Zionist and B’nai B’rith youth organizations who hoped to build a private Jewish summer camp in the South when they returned from World War II. While conducting research for their business venture, Herman and Ben Popkin consulted with owners of non-Jewish camps in north Georgia. Jane McConnell of Camp Cherokee was “honest and straightforward” and gave the Popkins this advice: “You boys ought to do it. There’s a need for a camp like the one you propose, especially for older children. Most private camps down south won’t accept Jewish children, and those that do, do so on a strict quota basis.”13 As Eli Evans, a former Blue Star camper, described in The Provincials, his classic memoir of the Jewish South, “Herman and Harry Popkin . . . built a veritable camping empire in the postwar era.”14 It was a southern Jewish mountain paradise for young boys like Evans—a magical world of bonfires, hiking, Israeli folk dancing taught by actual Israelis, Jewish girls, and deep discussions about God and Jewish identity. “For the rest of our days, it seemed,” wrote Evans, “one sure way that Jewish kids all over the South could start a long conversation was by asking, ‘What years were you at Blue Star?’”15

Although their Jewish educational methodologies differed—Camp Blue Star’s commitment to Jewish education was front and center in their daily programming, while Camp Wah-Kon-Dah’s Jewish ideology was expressed in “values,” rather than overt curriculum—the two camps are joined by their founders’ commitment to providing the highest quality, private camping experience for Jewish children. Ben Kessler was in the business of building strong Jewish youth. But Kessler did not focus on Jewish identity. At Wah-Kon-Dah—an Indian name that referred to “the Great Spirit” of the Omaha tribes—the focus was less on Judaism and more on the American frontier.

Early leaders in Jewish camping adopted the same American Indian folklore and heritage that so deeply influenced American camping at the turn of the 20th century.16 Founders of Jewish camps frequently adopted the names of local Indian tribes for their institutions, or used initials or even a Hebrew word, to create an Indian-sounding name with a Jewish back-story.17 Folklorist Rayna Green argues, “One of the oldest and most pervasive forms of American cultural expression is the “performance of ‘playing Indian.’”18 It began with Pocahontas rescuing Captain John Smith, the first Thanksgiving, and Squanto saving the Pilgrims. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s Hiawatha (1855) helped to solidify the image of the Indian in the American imagination. Victorian-era societies like the Elks, the Lions, and the Kiwanis introduced the idea of “playing Indian” to the white middle-class. The Boy Scouts, founded in 1908, was yet another expression of “playing Indian.” Indians represented the scouting ideal of manly independence. These themes were perpetuated in summer camps, and Jewish camps embraced this celebration of Native American culture.

Ben Kessler, a child of immigrant parents, veteran of World War II, and witness to the tragic losses of the Holocaust, created a summer world where Jewish children learned confidence, team work, and respect for God. No one ever forgot Ben Kessler’s motto that hung from a cross beam in the dining lodge: “God first—you second—me third.” There were no Friday evening Sabbath services at Wah-Kon-Dah. Instead campers gathered at “Inspiration Point” each Sunday morning, dressed in starched “whites” for a sermon from Uncle Benny, who was a master storyteller. He wove Indian tales with lessons about team spirit, loyalty, kindness, and respect for nature. Sunday services were followed by a noon-time meal of southern fried chicken, mashed potatoes, peas, and red Jell-O. George Buckner, an African-American chef, ran the kitchen at Wah-Kon-Dah for more than 30 years.

The Jewish Community Center of St. Louis acquired Wah-Kon-Dah in 1969 after a group of Jewish benefactors purchased the facility, re-named it Camp Sabra, and donated the camp to their community in 1970. Cabin names changed from Osage and Kickapoo to Habonim and Golan. Israeli youth led dance workshops and song sessions. Shabbat replaced Sunday. Gone were the lunchtime pizza burgers—a startling introduction to the kosher dietary laws in which meat and milk never came together on a bun.

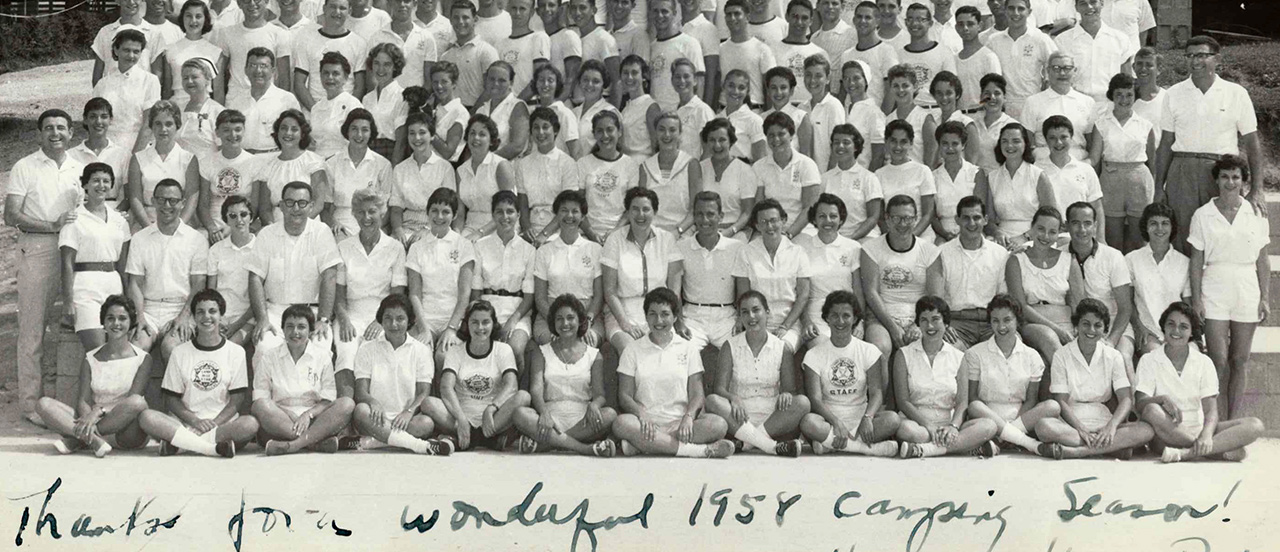

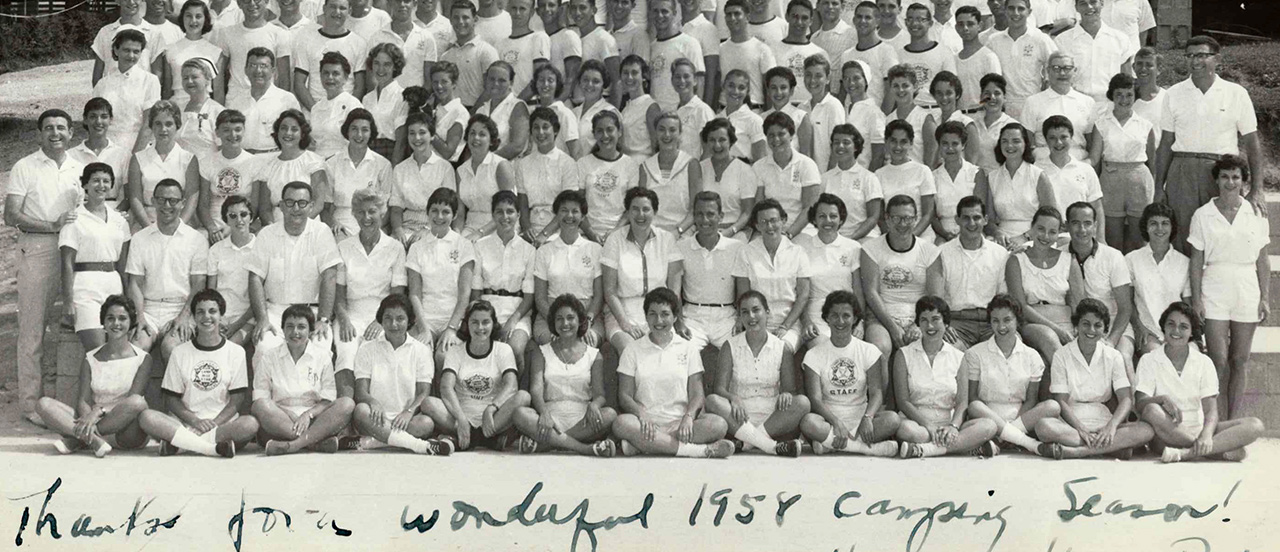

Jewish youth, staff, and parents alike experienced a profound sense of belonging at Jewish camps across the South, whether for two weeks or two months. An intricate network of southern Jewish relationships created in the summer influenced college decisions, future careers, religious involvement, romance, and the next generation of Jewish youth. Many campers and counselors grew into future leaders of the Jewish South’s local and regional organizations, historical societies, museums, programs for youth, and synagogues. Campers took their summer experiences of Jewishness back home and revitalized the Jewish worlds from which they came.

___________________________

NOTES

1. Jonathan D. Sarna, “The Crucial Decade in Jewish Camping,” 29–30, and Gary P. Zola, “Jewish Camping and Its Relationship to the Organized Camping Movement in America,” 2, in A Place of Our Own: The Rise of Reform Jewish Camping, eds. Michael M. Lorge and Gary P. Zola, (Tuscaloosa, AL: The University of Alabama Press, 2006); Nancy Mykoff, “Summer Camping,” Jewish Women in America: An Historical Encyclopedia, eds. Paula E. Hyman and Deborah Dash Moore (New York: Routledge, 1997), 1359–64; Amy L. Sales and Leonard Saxe, How Goodly Are Thy Tents: Summer Camps as Jewish Socializing Experiences (University Press of New England, 2004), 142–3.

2. Zola, “Jewish Camping,” 19.

3. In the early 1930s, I. D. Blumenthal, a successful Jewish businessman from Charlotte, bought Wildacres from Thomas Dixon, who had purchased the property with film royalties from D. W. Griffith’s controversial Hollywood epic, Birth of a Nation (1915), based on Dixon’s novel, The Clansman. Dixon invested heavily in the property and after losing a great deal of money when the stock market crashed in 1929, was forced to sell the 1,400 acres at a much-reduced price. In his essay on the history of American Jewish camping, Jonathan Sarna notes that the availability of affordable land and real estate in this era allowed many Jewish institutions and individuals to purchase affordable land for camps and retreats. Sarna, “Crucial Decade in Jewish Camping,” 37; Wildacres Retreat, “The History of Wildacres,” http://wildacres.org/about/history.html.

4. Sarna, “Crucial Decade in Jewish Camping,” 28–31; Sales and Saxe, How Goodly Are Thy Tents, 26.

5. Sales and Saxe, How Goodly Are Thy Tents, 26.

6. Ibid., 46.

7. Stuart Rockoff, “Henry S. Jacobs Camp, Utica, Mississippi,” Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities, http://www.isjl.org/history/archive/ms/utica.htm.

8. “Camp Blue Star,” “Southern Jewish Summer Camp: Camps in the Region,” Deep South Jewish Voice, January 2010, 28.

9. Jewish summer camps in the South include Camp Barney Medintz, a residential summer camp for the Marcus Jewish Community Center in Atlanta, founded in the 1960s and located in north GA; Camp Blue Star, Hendersonville, NC (1948); Camp Coleman, a program of the Union of Reform Judaism, Cleveland, Georgia (1964); Camp Darom, a project of the Baron Hirsch Congregation, Wildersville, TN (1981); Camp Henry S. Jacobs, a program of the Union of Reform Judaism, Utica, MS (1970); Camp Judaea, a program of Hadassah, the Women’s Zionist Organization of America, Hendersonville, NC (1960); Camp Ramah Darom (Ramah of the South), GA (1997); and Camp Sabra, a project of the St. Louis Jewish Community Center, Rocky Mount, MO (1970).

10. Camp Darom website: http://www.campdarom.com/index.html.

11. Lee J. Green, “Cold Outside But Time to Plan for Summer Camp,” Deep South Jewish Voice, January 2008, 26. Today, over 750 campers and 300 staff attend Blue Star’s six camps each summer. To read more about Camp Blue Star and other Jewish camps’ influence on southern Jewish life, see Leonard Rogoff’s important history of Jewish life in North Carolina, Down Home: Jewish Life in North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010) 279–81.

12. Sarna, “Crucial Decade in Jewish Camping,” 36.

13. Herman M. Popkin, Once Upon a Summer: Blue Star Camps—Fifty Years of Memories (Fort Lauderdale: Venture Press, 1997), 185.

14. Eli N. Evans, The Provincials: A Personal History of Jews in the South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1973/2005), 148.

15. Ibid., 150.

16. For an excellent discussion of the American camping movement’s association with Native American folklore, and its expression in Jewish camping, see Gary Zola’s analysis of Progressive Era educators/writers/camping enthusiasts, Ernest Thompson Seton and Luther and Charlotte Gulick, in “Jewish Camping,” 9–14.

17. Zola, “Jewish Camping,” 13–16. Zola gives examples of “American Jewish camps [that] took Native American–sounding monikers: Cayuga, Dalmaqua, Jekoce, Kennebec, Kawaga, Ramapo, Seneca, Tamarack, Wakitan, Wehaha, Winadu, and others.” Consider Camp CEJWIN, Port Jervis, NY—founded in 1919 by the Central Jewish Institute, and Camp Modin, founded in Belgrade, ME, in 1922 by Jewish educators Isaac and Libbie Berkson and Alexander and Julia Dushkin. Modin, located between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, is associated with the story of Hanukkah and the great heroism of the Maccabees.

18. Rayna Green, “Poor Lo and Dusky Ramona: Scenes from an Album of Indian America” in Folk Roots, New Roots: Folklore in American Life, eds. Jane S. Becker and Barbara Franco (Lexington, MA: Museum of Our National Heritage, 1988) 79, 80, 82, 83, 93.