Collections

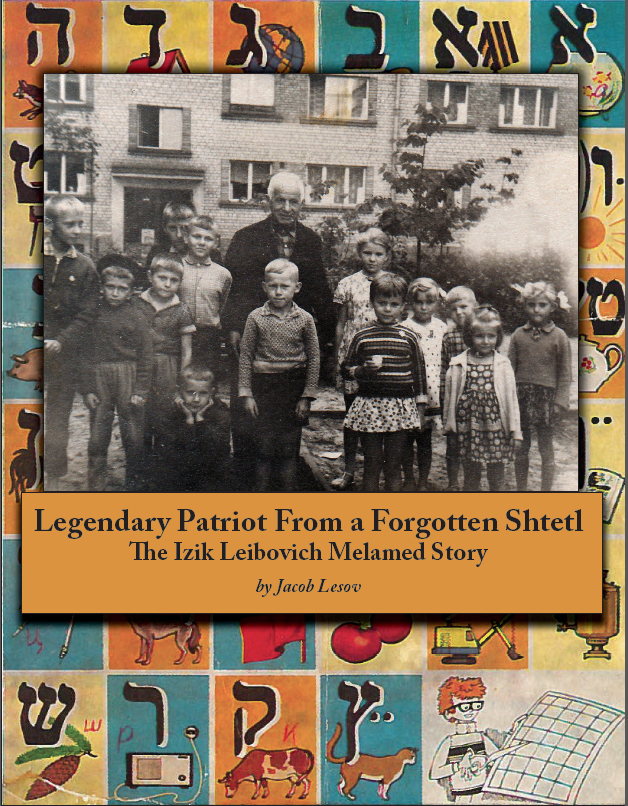

Legendary Patriot From a Forgotten Shtetl

The Izik Leibovich Melamed Story

by Jacob Lesov

Click on Cover to Read Story

To print the story, save the opened PDF file to your computer and then open it and print.

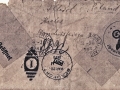

Yiddish Letters From Kielce and Lodz, Poland During the Nazi Era

Envelope Nazi Markings: “Geoffnet” – Opened; “Obercommando Wermacht” with Eagle perched above Nazi Swastika – Censirship Stamp.

Letter: Kielce February 29, 1940

Dear Aunt*,

We received your letter. We are all healthy and we all greet you from afar – from your sister’s son. Chaim (Brother of Helen Lipton, Beaufort, SC) and his family are in Kielce. From Uncle Gabriel (Bother of Helen Lipton) we got a letter and Uncle Chaim answered him.

We greet you, all of you. Please send him (Gabriel Stern, Columbia, SC) greetings from all.

Your sister’s son,

Dufchie (David or Dovid)

*Aunt: Helen Lipton, the mother of Joseph Lipton

Translation of Letter and Envelope Markings

Translator: Rabbi Philip Silverstein

Columbia, SC

The Desk

Written by Joseph Lipton

This is the improbable story of a desk that has been and continues to be an extended part of my life. It resided in the hallway of my parents’ home in Beaufort, S.C. When my mother died in 1987 that desk would find its place in my home in Columbia, S.C. It is not a valuable piece of furniture in and of itself. It does not claim any special lineage or provenance. So why would it tug at my heartstrings? Because it has been for over three-quarters of a century the keeper of memories. Everything that has now grown precious with time found its way into the sheltered safety of that desk. It was the oasis where my mother would settle to read, with me at her knee, amid a rivulet of tears and trembling sobs, the Yiddish letters from her mother, her brother and sisters and her nephews and nieces who lived in Kielce and Lodz, Poland.

In the year 2007 as I sat at the desk the memories that it symbolized were resurrected. I looked at the drawers, unopened for decades and decades. Be careful was the cautionary warning. Open the bottom drawer and you will be entering the past. Yes, but if not now – when? Time passes and the moment is gone.

I reached for the pulls and open the drawer. There they were, three quarters of a century later, letters from the Bubba, the Uncles, the Aunts and the cousins who lived in Kielce and Lodz, Poland addressed to my mother, Helen Lipton, Beaufort, S.C. and to my Uncle Gabriel Stem, Columbia, S.C., written in the mamaloshen.

As my hand fished in the drawer it lighted upon the ubiquitous group photograph of my mother’s family. Seems that practically all of my American relatives have a copy of that picture which harbored 18 relatives within its four comers, taken in 1925. At the center of the sepia photo sits the Zadye and the Bubba. Time after time my mother, while pointing to each figure, would identify each one. This exercise became for me a ritual. Today I am the only member of the clan who can pin a name to the relatives of Poland. This knowledge proved a facilitating tool in the translation process. More so that picture fueled incentive to translate the letters in that desk.

Across the span of time to the year 2007 the dybbuk of these kin have mysteriously taken possession of me. My release from its grip is contingent upon the translation of these Yiddish letters.

Thus driven I gently disentomb these fragile scraps of paper that awaken memories that always hovered at the rim of consciousness. As I carefully removed the faded, yellowed, tattered correspondence I thought, I too have grown old along with the Bintel Brief that I guarded and protected for so many decades. Oh, the ravages of time. The Yiddish poet Khonon Eager revealed, in poetry, a stark description of man’s greatest enemy – time. “Der greste ganev is di tsayt.” (The biggest thief is time).

With the dybbuk nipping at my heels; what to do with these letters? Where to turn? To whom shall I turn? Who can translate Yiddish into English? No small problem in South Carolina. Like the extinction of flora and fauna so too native languages are disappearing daily. The Yiddish shprach is on the endangered list. In South Carolina it is disemboweled from speech, from writing, from reading, from literature and from thought. I was faced with the real possibility that these letters would remain dumb. I was desperate. Before I returned to dust I wanted to have this material translated into English and the characters mentioned therein correctly identified and their connection to the Stern-Lipton families clearly established. This meant that I, perhaps the only living relative who can satisfy these self-imposed requirements, must partner with a translator. For convenience and efficacy the translator, for my purpose, should be one who resides in Columbia.

Obviously, the translator must be thoroughly fluent and competent in the two languages that are the subject of consideration. Obstacles are endless and varied. For example, while Yiddish shprach was the universal vernacular of European Jews prior to World War II uniformity was not prevailing. Diction and dialect varied from one locale to another. Then there are idioms that must be deciphered. Add to this the complications of handwriting and misspelled words. The letters in my possession were written by Polish Jews. This means that one encounters a Polish word written in Yiddish. The complexity unfortunately does not end there. Because of the proximity of Poland to Germany a word from that country will find its way into the correspondence as well as on occasion a word in Hebrew – all written in Yiddish. As a result dictionaries are an absolute necessity to the process – Yiddish, Hebrew, German, and Polish in this instance. A calendar conversion table is useful to convert Hebrew dates into the Gregorian calendar. Finally, the ultimate decision is whether the translation should be rendered literary or literal. I opted to transcribe the letters literally. There is a word in Yiddish called “taam”. Loosely translated it means taste. I was fearful that a literary translation would not be true to their essence and that they would lose their style, quaintness, flavor and “taam”.

When dealing with personal correspondence it is essential that a knowledgeable possessor of the letters sit with the translator. I was indeed fortunate, perhaps lucky is the word, in finding and forming not only a close, valued friendship but a compatible working relationship with Rabbi Philip Silverstein of Columbia, S.C. With amazing skill he deftly translated the gnarled Yiddish of some thirty odd letters at this date. Also he has taken a lively interest in the Stern family – past and present. It is my sad guess that Rabbi Silverstein is the only person in the state who possesses the required capability, competency and knowledge to translate Yiddish into English. One can easily awaken to the startling realization that here are a people without a native language. So immersed into the host culture that elements of one’s own distinctive tools of identity are disappearing.

There is in this cache of letters and post cards a record of the travails of one family in the decade of the 1930s. As Mark Anthony warned, “If you have tears, prepare to shed them now.” Aside from family news there is the betrayal of emotions that alternate between longing and desperation – hope and disappointment – light and darkness. And then on September 1, 1939 darkness descended upon the Jews of Poland. The most devastating pogrom in Jewish history commenced.

It is now 1940 the last letter from the blackness of Poland arrives in Beaufort, S.C. from Sura Sterenzys Albirt of Kieice, Poland to her sister Helen Lipton dated February 29, 1940. The Germans are at this time fully entrenched and control and operate the postal service. The envelope bears the Nazi seal of censorship with the invasive word “Geoffnet” (opened). A second censorship stamp reads, “Ober Commando Wermacht” with eagle perched above a Nazi Swastika. The contents reveal an innocuous message that they are all doing well. No elaboration.

Prior to the last communication, the letters contain pleas for immigration papers to enable them to travel to America. In another, my Grandmother Rivke Machele Sterenzys is chastising her son Gabriel Stern of Columbia, S.C. for not writing, and then in the character of a yente she tells of an ancient Aunt about to remarry. In sum, to me at least, a reminder that Jewish life existed prior to the apotheosis of the Holocaust. A world where Yiddin created a tradition and a culture of study and learning – of literature, music, theatre – a world of day to day life. Jews today are submerged in a miasma of amnesia regarding that period prior to World War II.

To mitigate the handling and to facilitate reading, enlarged copies are made of each letter. Seated facing one another across a small desk in the Rabbi’s book lined study we open a Yiddish letter for the morning translation. A solemn tranquility enshrouds the Rabbi as he applies complete concentration to the task at hand. Suddenly there emanates from him a burst signifying conquest and then a smile of satisfaction spreads across his face. “I’ve got it” he explodes and I’m ready to record the first words. Suddenly the dead come alive when the Rabbi intones “Lieber tyerer tochter” (my dearest daughter). My grandmother, Rivke of Kieice is speaking to her daughter, my mother, Helen of Beaufort. Imagine!

What makes that opening line so deeply emotional and so incredibly poignant is that I, in 1931, at the age of eight with my mother and younger brother were in Kieice and Lodz visiting our kin. Like the traditional Yiddisher Mama Rivke is imploring her daughter Helen, in a lengthy letter, to take care of herself and not to cry and make herself sick. She reminds her daughter that she is not a child anymore but a woman and that she must think about her husband and her little children and not think only of them. You must realize, Rivke continues, that your parents are old people – 75 years old. She adds philosophically, “You are after all still a young woman just entering the world and you have to bring up your dear children. You must not become sick from your thoughts about your father dying. Only God can help.” Using the anaphoric rhetorical style she advises, “No one, no doctor, no person, no children only the one God in heaven can help.”

In a lighter vein perhaps in unintended humor my grandmother in the same letter relates that Aunt Malka Leah is getting married and that all the children agree to the marriage. And then she describes the Aunt’s conduct. “She goes dressed like a twenty year old flirt with breast holders like a young girl – she is 71 years old. And imagine she still has the desire to take on a man.”

In another letter Rivke chastises her son, Gabriel Stern, for not writing and asks at the same time that he should send immigration papers and a ships card so that Dufchie, her grandson, may travel to America, “di Goldene Medina”. The ships card was sent but alas Dufchie’s dream was not to be – “tsu shpat” (too late). The Nazis and the newly abridged American quota system spelled the denouement to Polish Jewry. Dufchie and his brother escaped to Samarkand, Russia where they survived the war and the Great Pogrom. After the war Dufchie returned to Poland to locate members of his family but was murdered in the Kieice Pogrom.

I have lived with these family letters, family photographs, my mother’s passports and other memorabilia for three quarters of a century. Daily I have confronted the past and the dead. Some questions have been answered but more remain and will forever remain unanswered because in youth we failed to ask questions. These letters and memories stir the heart and bring a dampness to the eye. As one grows old one begins to understand the truth of Sophocles insight, “It is the dead, not the living, who make the longest demand. We die forever.”

My grandmother always closed her letters with these words, “I greet you and kiss you my dear children from the depths of my heart.”

Text written by Joseph Lipton/ Edited by Nancy Lipton