I am grateful for the opportunity at the upcoming May event on World War II to speak for my father, the late Alan Jay Reyner. In some ways it is an awkward situation for me as I’m not sure I am worthy to speak about a matter so personal to him that only he and others who shared his experiences could fully comprehend.

After my father died in 1974, I found a nine-page memoir he wrote shortly after the war. Like most of the men and women who went overseas it was something he simply did not talk about. Save one memorable night in the ’60s in a hotel room in Paris, he never spoke to us about his experiences and very little to close friends and fellow soldiers. Time permitting, perhaps more about that evening in Paris and its origins at our meeting the first weekend in May.

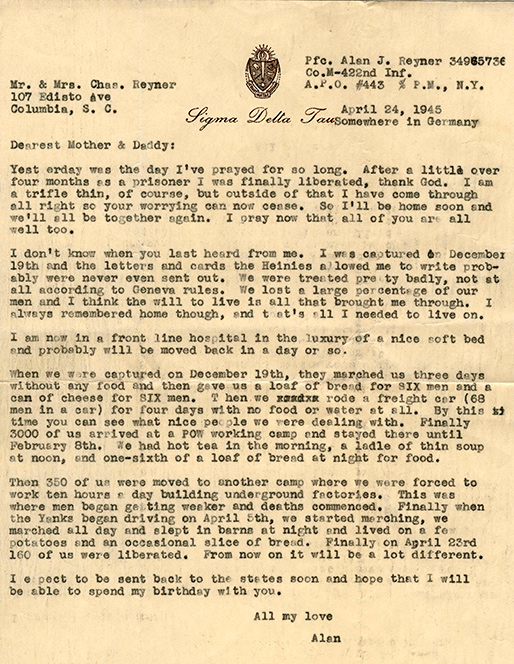

My father was a combat soldier. He was assigned to the 422nd Regiment of the 106th Infantry Division. He was a machine gunner; his rank, private first class. That’s about as basic as it gets. Most of the enlisted men of the 106th were college-age boys who had never seen combat. Certainly that was my father’s case—before entering the army my father led a fairly sheltered life as an 18-year-old college student at the Wharton School of Finance in Philadelphia. In the fall of 1944, when he was 19, my father was shipped to the front to relieve, in his words, the “ninth Infantry regiment of the crack 2nd Division.” At the time of the commencement of the Battle of the Bulge at dawn on December 16, 1944, his regiment was the deepest outfit in the Siegfried Line. When the fighting began he was just outside the Belgian village of St. Vith, approximately 30 miles northeast of Bastogne. He was right smack on the front lines.

The 422nd and 423rd regiments, as well as the rest of the 106th, were vastly out-manned and out-gunned from the get-go. Combat for my dad began on the way to the front on December 9, 1944, with the most intense fighting experienced by his unit at the Bulge lasting only four days; but, by all accounts, his last day of combat, December 19th, was really hell. In my father’s words: “Things were getting more and more confused by then. Our own mortars were shelling us, inflicting heavy casualties. It was then that I really saw what a bullet could do. Men were lying all around me, wounded and dying, others were shocked out of their speech capacity, others were simply walking around hollow-eyed. None of us could believe that this was happening to us.”

History records the Battle of the Bulge as the greatest American loss ever on foreign soil; 19,000 Americans were killed, 47,500 wounded, and 23,000 Americans were captured or missing, my father amongst them.

History records the Battle of the Bulge as the greatest American loss ever on foreign soil; 19,000 Americans were killed, 47,500 wounded, and 23,000 Americans were captured or missing, my father amongst them.

When I found my father’s memoirs, I can’t say it really meant a lot to me other than the fact that I, of course, was understandably proud of his service and his personal conduct. As kids, my brother, Jeff, and I would find old war memorabilia in a chest in the attic, but it was something that was never really discussed. Unlike many of my friends’ fathers, my dad never took up hunting or owned a gun. He was very uncomfortable when our uncle, an avid hunter, gave my brother and me shotguns. Simply put, my father had seen too much killing during the war.

Approximately 20 years after Dad died, during the spring of 1995, I received a call from a retired army chaplain named Tom Grove who also was captured at the Bulge, and he enlightened me as to my father’s “real experiences” in WW II. One thing led to another, and I spent a large amount of time tracking down his war buddies. I talked to some 25 of them and got the opportunity to meet with two—one of whom, believe it or not, was actually a neighbor. That in itself is a very interesting story, which I will share with you in May. It turns out that although my father’s accounts were accurate to a fault, he wrote with considerable restraint and omitted important facts. When the details were filled in by historians as well as his war buddies, a totally different picture emerged. To this day it amazes me how something so historically accurate didn’t reveal anything about the “story behind the story.” Understating events pertaining to themselves seems to be the norm for his generation. The term “selfie” was simply not in their vernacular.

As I mentioned, Dad was among the thousands of Americans captured by the Germans. They were loaded up in boxcars—68 men to a car—and sent to Stalag IX-B in Bad Orb, Germany, by all accounts, one of the worst POW camps in Europe. The boxcars were strafed by Allied planes and many men were lost en route to Bad Orb. As bad as that was, it is what happened next that made his experiences so unusual.

He was at IX-B a little over a month when, because of his religion, he and some 350 other POWs were transferred to Berga am Elster, a sub-camp of Buchenwald. Of the 350 prisoners, 70 to 80 were Jewish. The rest had Jewish-sounding names, looked Jewish, were troublemakers, or just happened to be selected to fill the Nazi quota of 350. Berga made IX-B look like the Ritz. It was a slave labor camp with political prisoners, in contravention of the Geneva Convention, not a POW camp. More than 20 percent of the American POWs at Berga died within a three-month period. It was simple: the prisoners walked an hour to and from the work site, where the guards forced them to labor ten hours a day digging tunnels for an underground factory, feeding them only a liter of watery soup and a piece of bread a day. Again in my father’s words: “If we took one minute’s rest, we were beaten with a shovel or spiked with a pick. All the foremen carried rubber hoses which they didn’t mind using. I had no idea men could be so bestial. One man was struck in the head with a shovel and became blind. In trying to help him, I was hit in the hand, a blow which caused an infection which lasted many weeks.

“Conditions among our men were as bad as can be imagined. We had reached the stage of animals . . . stealing, hating, and fighting among ourselves. I still pride myself in the fact that I could maintain my honor and some sense of self-respect. It became so bad that even sick men had their food stolen from them before they could even get it.”

Within a month, because of slow starvation and back-breaking work, “the deaths began.” My father escaped from camp by jumping in the river at night during a black-out and floating downstream, but after six days was recaptured. His second escape—this time successful—was just seven days from liberation. I am convinced the first escape, while risky, saved his life. While trying to get back to Allied lines, he stole chickens, rabbits, eggs, milk, and vegetables from farmers. He wrote, “We really fared well.” At the time of his second escape and upon his liberation he weighed less than 95 pounds.

Just before he died, the award-winning Charles Guggenheim, a member of the 106th, wrote and directed, along with his daughter Grace, a moving PBS documentary entitled “Berga: Soldiers of Another War” depicting the experiences of the combat soldiers who were captured at the Bulge and sent to Stalag IX-B and then Berga. It haunted Guggenheim, who was born into a prominent German Jewish family, that because of a severe foot infection he remained stateside and escaped combat and Berga. According to the documentary, Guggenheim “carried with him a personal and moral obligation for more than fifty years to tell this untold story for his comrades who did not return, and for those who lived with the horror of their experience.”

Mitchell Bard of the American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise (AICE) published a book titled Forgotten Victims: The Abandonment of Americans in Hitler’s Camps, in which he references my father and a document he provided to the War Crimes Office for the prosecution of the guards for the death of Bernard Vogel. Vogel was a Jewish soldier at Berga who escaped, was recaptured, and was forced to stand outside the POW barracks in the freezing cold for two days with no food or water as punishment for trying to escape. Vogel died shortly thereafter in the arms of a fellow prisoner, an army medic.

One wonders how the United States could, in the winter of 1944, send into battle American Jewish soldiers—more than 550,000—many of whom were fighting the Nazis with an “H” on their dog tags, the “H” standing for Hebrew. Many Jewish POWs threw their dog tags away. As one prisoner in the Guggenheim documentary said to himself when asked by the Nazis if he was Jewish, “Hell I was born a Jew. I may as well die a Jew.”

As mentioned, I talked to some 25 of Dad’s fellow combat soldiers who were prisoners of war at Berga and most have lived wonderful, productive lives. I sensed from my phone conversations and the letters I received from them they were special people, quiet heroes and true survivors in the finest sense of the word. That is certainly how I remember my father.