B’nai Israel

146 Heywood Ave

Spartanburg, SC 29302

Year Built: First synagogue: 1917 | Current synagogue: 1963

Architect: Unknown

Years Active: 1912-Present

Congregation History

Early Jewish Settlers in Spartanburg

Spartanburg, South Carolina, located at the edge of the Blue Ridge Mountains, was established in the mid-18th century.1 The British acquired the region from the Cherokee tribe via treaty in 1753, intending to establish agriculture and textile manufacturing in the area. There is evidence that Jews were living in Spartanburg as early as 1878, though their identities are unknown.2 The first known record of a Jewish family living in Spartanburg relates to the Greenewald family. Moses Greenewald was the first of his four brothers to relocate to Spartanburg from their hometown, Wilmington, North Carolina.3 Records from 1882 indicate he was living in Spartanburg and had served as captain of the volunteer Spartanburg Fire Engine Co. In the late 1880s, his brother David joined him.4 Moses Greenewald opened the first Jewish-owned business in Spartanburg in 1886.5 His store was called M. Greenewald, Outfitters to Men and Boys.

Between 1890 and 1920, Spartanburg’s population grew with the expansion of the textile industry, which served as one of South Carolina’s leading producers of cotton.6 The Jewish population, however, did not grow substantially until the turn of the 20th century, when greater numbers of Eastern European immigrants began moving to the south in search of new business opportunities.7 Many Jewish migrants were ultimately successful and paved the path for their children, first-generation Jewish-Americans, to live prosperous lives of their own. One daughter of a Jewish immigrant of note is Dr. L. Rosa Hirschmann, who began practicing medicine in Spartanburg in 1903. She was the first of two female graduates to graduate from the Medical College of South Carolina (now MUSC) and became Spartanburg’s first female doctor.8

Organized Jewish Life

Very little is known about Jewish religious life in Spartanburg prior to the 20th century. Evidence of organized religious practice in Spartanburg first appears in The Carolina Spartan. The article from 1888 offers evidence of a “Hebrew Friends” meeting for Yom Kippur, which suggests that even before Spartanburg’s Jewish community officially organized, they still gathered to worship and celebrate high Holy Days together.9 Current members of Congregation B’nai Israel suggest that by 1905, Spartanburg’s Jewish community was large enough to form a minyan, thus marking the beginning of the town’s “active Jewish community.” In 1912, a group of approximately twelve families came together to draft the constitution and bylaws of their new congregation, Sirh Israel.10 According to Spartanburg’s City Directories, the small congregation met at Abe Goldberg’s clothing store on West Main Street.11 Reverend Craft, an itinerant rabbi, led the congregation until he died in 1914. The congregation subsequently hired an East European immigrant and Orthodox rabbi, Samuel Cohen, who served from 1914 until 1916.12

In 1916, Sirh Israel had grown to 27 members and filed for incorporation under the leadership of Joel Spigel, Hyman Ougust, and Joseph Miller.13 They adopted the name B’nai Israel, which the congregation has used ever since. Rabbi Jacob Raisin of Charleston’s Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim visited Spartanburg that year to assist with the congregation’s fundraising efforts for the synagogue.14 Spartanburg’s first synagogue was designated to be built on the corner of Dean and Union Streets. While the synagogue was under construction, services continued to be held above Goldberg’s store. Sunday school classes, organized by Joseph Jacobs, were held by Mrs. Futchler in her living room. Dr. Rosa Hirschmann Gantt, the first president of the Ladies Auxiliary Society, organized a fundraiser for pews and stained glass windows for the synagogue. With the growth of the congregation, which had doubled in size since 1912, they were able to fund the construction of the synagogue.15 The women took it upon themselves to finish the basement floors and patch and paint the walls so that the children would have a designated study space of their own.16 The synagogue was completed in 1917 and opened just in time for High Holy Day services that year.17 The congregation followed a mixture of Orthodox and Reform traditions to accommodate everyone, especially during the High Holy Days. For example, Dr. Finklestein led Reform services one day in English and Dr. Isaiah Sobell led Orthodox services in Hebrew both days.18 The Jewish population of Spartanburg, an estimated 80 people, came together to establish a Jewish section in Spartanburg’s Oakwood Cemetery in 1924.19 Dr. Rosa Gantt was instrumental in negotiating with Oakwood Cemetery to provide the section.20

World War I and World War II

The Jewish population of Spartanburg fluctuated throughout the 1920s and 1930s, mostly on account of the Great Depression. Some local merchants left Spartanburg to try their luck elsewhere, and those who stayed eventually went bankrupt.21 Throughout the 1930s, the congregation of 36 members supported each other. The Sisterhood Minutes Book, which belonged to Daisy Spigel, reveals that the Sisterhood lost all of its money when the local bank failed. In response, the women hosted bridge parties to offset the deficit and provide support to the Temple.22 As a result, the congregation was able to support their rabbi throughout the Depression and, in 1937, Joseph Spigel was finally able to pay off the mortgage on the synagogue.23 He subsequently burnt the mortgage.24 Approximately 100 Jews lived in Spartanburg by the end of 1937.25

During World War I, many Jewish servicemen were stationed in the area at Camp Wadsworth. Jewish soldiers would either hold services in an old church near Camp Wadsworth on the western side of Spartanburg or travel to attend B’nai Israel on the east side.26 During World War II, the camp nearest Spartanburg was Camp Croft. The camp, which opened in January 1941, was one of the US Army’s principal Infantry Replacement Training Center (IRTC) and also served as a POW camp.27 Jewish soldiers who were stationed at Camp Croft in WWII frequented B’nai Israel more often.28

The end of World War II marked a transition for the town of Spartanburg. The economy shifted from agriculture and textile manufacturing to a high-tech industry economy.29 Many Jewish servicemen who had been stationed near Spartanburg returned to establish businesses after the war.30 In 1947, the Jewish population stood at 170 individuals, nearly doubling over the last twenty years.31

A New Synagogue for Spartanburg

In the 1950s, Abe Smith purchased a 7-acre lot on Heywood Street where he intended to build a house for his family.32 Spartanburg’s Jewish population was growing and the congregation was beginning to outgrow its original synagogue. Members of the Jewish community suggested to Smith that the land would be better suited for the new temple and he agreed.33 The congregation purchased the land from Smith in 1953 to construct a new B’nai Israel Temple.34 A Victorian home already stood on the 7-acre lot; the congregation converted the existing building into a Sunday school and social hall, which later became the B’nai Israel Center. In 1954, the B’nai Israel congregation established a new Jewish Cemetery within Spartanburg’s Greenlawn Gardens, which eventually became the B’nai Israel Memorial Gardens.35

B’nai Israel sold the original Dean Street synagogue in 1961 and the new Heywood Street Synagogue opened in 1963. While the new synagogue was under construction, services were temporarily held at the B’nai Israel Center for two years. In the meantime, the congregation also kept the Torah scrolls housed there. The center served as a site for the congregation’s social events, B’nai mitzvahs, and holiday events.36 The congregation had also outgrown the center and the Sunday school by 1971, however, and moved to a new education building on the 7-acre lot.

The congregation hired Rabbi Max Stauber in 1955, who served Spartanburg for the next 30 years.37 By this point, B’nai Israel had begun to follow the Conservative tradition, although, unofficially, they served Jews of various denominational affiliations to appeal to the community.38 Rabbi Stauber continued to lead services when needed after his retirement in 1983. He passed away in 1986.39

B’nai Israel Today

B’nai Israel formally adopted the Reform tradition in 1994 when the congregation joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations.40 At the time, over 100 families belonged to the congregation. Rabbi and Cantor Samuel Cohon assisted the congregation through the transition and incorporated some of their existing prayers into the new prayer books.41 Susan Abelkop was elected in 1998 to the congregation as the first and only female president and went on to hold office within the congregation twice.42 While the high-tech sector of Spartanburg keeps attracting people to the area to settle and build their families, the Jewish population is dwindling. There is hope, however, that as Spartanburg continues to grow and evolve, this up-and-coming town will once again be a hub for southern Jewish life again.

Architectural Description

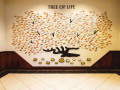

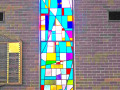

The current building that houses Congregation B’nai Israel is a multi-level, mid-century modern structure built in 1963. Like most structures built in the 1950s- 70s, the synagogue boasts a variety of architectural details from popular styles of the time, including International Modern, Contemporary Modern, and of course, Mid-century Modern. The structure has a flat roof with many picture windows. Some of the windows, such as those in the sanctuary, are stained-glass, while the others are used primarily for letting as much natural light into the building as possible. The architect used a mixture of brick, concrete, natural stone, and glass to create the façade of Temple B’nai Israel. The front door of the synagogue is a double wooden door with two stained-glass windows flanking the entrance. Directly behind the doors, you can see the top of the sanctuary, a two-story structure with high ceilings and stained-glass windows flush with the brick wall. The wall next to the front door features “Temple Beth Israel” with a large, metal menorah.

MST #1170: Congregation B’nai Israel, Spartanburg, SC

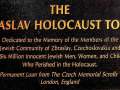

Congregation B’nai Israel in Spartanburg is home to Holocaust Memorial Scroll MST #1170. Immediately upon their invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1939, the Nazi regime began to persecute the Jewish inhabitants of the region. In 1941, the German authorities ordered all congregations in Bohemia and Moravia to send their religious artifacts to the Pinkas Synagogue in Prague.1 This order included Sifrei Torah like MST #1170. These objects remained in the basement of Pinkas until 1963 when they were rediscovered by the founders of the Memorial Scrolls Trust.2 The Trust’s mission is to research, restore, and redistribute these torahs throughout the world as a continuing [memorial] to the victims of the Holocaust. Spartanburg’s MST #1170 serves as a [monument] to the Jewish community of Zbraslav, a village in southern Moravia.

The Jewish community of Zbrasalv is first mentioned in the late 1600s, but the population did not peak until 1880 with 107 individuals.3 By 1930, this number was reduced to 42.4 The community’s last rabbi was Dr. Simon Adler (1884-1944), was deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto and then Auschwitz, where he perished.5 In 1997, his two surviving sons opened a museum in his birthplace of Dobrá Voda.6 Zbraslav’s final prayer house, located at Hauptova Street 8/599, was converted to apartments after the war and the community was not reestablished.7 MST #1170 was donated by Jay and Pamela Kaplan in February of 2001.8 It is held in a purpose-built display case in its new home at Congregation B’nai Israel alongside the original tag the Nazi authorities used to identify it.9 During high holidays, it is placed into the congregation’s ark, alongside their other torah scrolls.10

1. Memorial Scrolls Trust, “Our Story: Bohemia and Moravia,” Memorial Scrolls Trust, n.d., https://memorialscrollstrust.org/index.php/our-history/bohemia-moravia.

2. Memorial Scrolls Trust, “Our Story: London,” Memorial Scrolls Trust, n.d., https://memorialscrollstrust.org/index.php/our-history/london-new.

3. Jay Kaplan, “Holocaust Torah,” 2023.

4. Kaplan.

5. “Šimon Adler,” in Wikipedia, November 25, 2022, https://cs.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=%C5%A0imon_Adler&oldid=22004120; “Šimon Adler | Database of Victims | Holocaust,” accessed August 17, 2023, https://www.holocaust.cz/en/database-of-victims/victim/74541-simon-adler/.

6. “Museum of Dr. Šimon Adler in Dobrá Voda,” accessed August 17, 2023, https://www.sumavanet.cz/ki/su/fr.asp?tab=ki_su&id=1112&burl=&pt=TUMZ&lng=en.

7. Kaplan, “Holocaust Torah,” 2023.

8. Mark Packer, “Holocaust Torah,” August 6, 2023; Jewish Historical Society of South Carolina, “B’nai Israel,” n.d., https://jhssc.org/synagogue/bnai-israel/.

9. Packer, “Holocaust Torah,” August 6, 2023; Jewish Historical Society of South Carolina, “B’nai Israel.”

10. Packer, “Holocaust Torah,” August 6, 2023.

Endnotes

1-15. “ISJL – South Carolina Spartanburg Encyclopedia.” 2022. Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life. 2022.

16. “Our History – Temple B’nai Israel.” 2016. Ourtemple.net. October 31, 2016.

17-19. “ISJL – South Carolina Spartanburg Encyclopedia.” 2022. Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life. 2022.

20. “Our History – Temple B’nai Israel.” 2016. Ourtemple.net. October 31, 2016.

21. “ISJL – South Carolina Spartanburg Encyclopedia.” 2022. Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life. 2022.

22. “Our History – Temple B’nai Israel.” 2016. Ourtemple.net. October 31, 2016.

23. “ISJL – South Carolina Spartanburg Encyclopedia.” 2022. Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life. 2022.

24. “Our History – Temple B’nai Israel.” 2016. Ourtemple.net. October 31, 2016.

25. “ISJL – South Carolina Spartanburg Encyclopedia.” 2022. Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life. 2022.

26. “Our History – Temple B’nai Israel.” 2016. Ourtemple.net. October 31, 2016.

27. “Site History – Camp Croft.” 2022. Camp Croft. 2022. https://www.campcroft.net/site-history.

28. “Our History – Temple B’nai Israel.” 2016. Ourtemple.net. October 31, 2016.

29-31. “ISJL – South Carolina Spartanburg Encyclopedia.” 2022. Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life. 2022.

32-34. “Our History – Temple B’nai Israel.” 2016. Ourtemple.net. October 31, 2016.

35-38. “ISJL – South Carolina Spartanburg Encyclopedia.” 2022. Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life. 2022.

39. “Our History – Temple B’nai Israel.” 2016. Ourtemple.net. October 31, 2016.

40. “ISJL – South Carolina Spartanburg Encyclopedia.” 2022. Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life. 2022.

41-42. “Our History – Temple B’nai Israel.” 2016. Ourtemple.net. October 31, 2016.