Temple Sinai

11 Church St.

Sumter, SC 29150

Year Built: Originally built in 1904; rebuilt 1912-1913

Architect: Isaac Schwartz, H.D. Barnett, and Julian H. Levy (building committee)

Years Active: 1905-Present

Congregation History

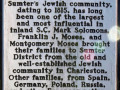

Early Jewish Life in Sumter

The first Jewish settler in Sumter, South Carolina, Mark Solomons, arrived in town sometime between 1815 and 1820, but the 1820s mark the beginning of what would be Sumter’s fast-growing Jewish community.1 Besides the Solomon family, other notable Jewish families who settled in Sumter in the mid-19th c. include the Moses, Harby, Cohen, and Moise families.2 Sumter’s Jewish population increased after the Civil War when East European immigrants began to call Sumter their home.3 As Sumter’s Jewish community grew, they began to establish Jewish organizations.

Organized Jewish Life

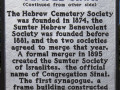

The Hebrew Cemetery Society was established in 1874 and their first order of business was to purchase land for a Jewish burial ground.4 Seven years later, in 1881, the Hebrew Cemetery Society merged with the Hebrew Benevolent Society under the Benevolent Society’s name.5 After being established, the newly constituted Benevolent Society members were eager to elect officers and formalize a constitution.6 Members elected Altamont Moses as the first president of the Hebrew Benevolent Society.7 The Society held its meetings in the Masonic Hall above J. Ryttenberg and Sons on the corner of Main Street and Liberty Street.8 In February of 1881, Reverend Mr. Levy spoke to the Benevolent Society about helping Russian refugees who were fleeing waves of violent pogroms in Tsarist Russia. The Society not only raised $160 in aid, but they also formed a Russian Aid Committee which helped Russian Jewish immigrants settle into their new homes and find jobs in Sumter.9

When the Cemetery Society and Benevolent Society merged in 1881, one of their first tasks-at-hand was to organize a Sunday school. By April of 1883, the Sunday school had 24 students.10 Rabbi David Levy of Charleston’s Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim synagogue traveled to Sumter each week to teach the confirmation class while the students, in return, would travel to Charleston for their confirmation ceremonies.11 In 1891, Miss Carrie Moses became the Sunday school’s superintendent.12

The Hebrew Benevolent Society merged in 1895 with the Sumter Society of Israelites (est. 1887), which is the official name of Congregation Sinai, with Altamont Moses continuing in the role of president.13 It became inactive at the turn of the century, but with a boost from the growing community, they were able to reorganize and hire their first full-time rabbi, Jacon Klein, in 1904.14 They built a wooden synagogue that same year on the corner of Hampton and Church Streets. It burned down sometime between 1904 and 1912, and was replaced with a brick structure in 1913 and is the home of Temple Sinai today.15

A Series of Rabbis

The Jewish population in Sumter was 89 individuals in 1878, but by 1905, that population had grown to 175 individuals.16 In 1907, however, the congregation only had 40 active members.17 Rabbi Klein served the congregation for four years before he resigned and was replaced by Rabbi David Sessler, who only served Temple Sinai for two years.18 Rabbi David Klein followed him, and served the congregation from 1910 to 1917.19 He also ran the Sinai Culture Society, established in October of 1910, which promoted the religious, social, and intellectual life of its members.20 They held “bimonthly lectures, poetry readings, and other programs inevitably ended with ‘delightful refreshments’ sponsored by the Sisterhood hostess of the evening.”21 All members of the congregation were eligible to join and its first meeting brought 24 members: 15 men and 9 women.22 By the summer of 1911, however, the group disbanded.23

Rabbi Ferdinand K. Hirsch became Temple Sinai’s rabbi in 1919.24 He also served Temple Beth El in Camden.25 Hirsch also ran the Sunday school, managed the cemetery, and handled the congregation’s philanthropy.26 He left the congregation in 1928 and was succeeded by Rabbi Hirsch L. Freund, who only stayed for two years.27

Social Life

The Jews of Sumter were relatively integrated into secular society. Reportedly, they experienced no significant antisemitism and interfaith dialogues and marriages were common in Sumter.28 Some families observed the Sabbath every week, whereas others only observed the holidays.29 Because of interfaith marriages, many families observed both Jewish and Christian holidays.30 Keeping kosher in Sumter was not practical because there was no local kosher butcher.31 During the Interwar Period, Jewish Sumterites actually saw a divide in their own greater Jewish community rather than between Jews and non-Jews. The Eastern European immigrants adapted to Reform Judaism, the earlier residents of Sephardic and German descent tended to align with Orthodox tradition.32 Because Temple Sinai was the only synagogue in Sumter, the two groups would simply sit on opposite sides of the synagogues, segregating themselves.33 It wasn’t until 1925 that Temple Sinai joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations.34

Interwar Period

Despite a recorded membership of 100 families in Temple Sinai’s congregation in 1926, attendance at weekly services and other congregational activities declined in the Interwar period.35 In 1927, the annual meeting minutes stated that the Sunday school was in “good condition” and that more than 30 children from Sumter and nearby Manning attended classes. Within five years, the enrollment had increased to 40 children and five teachers volunteered their services, suggesting that the plan to recruit from Bishopville in 1932 was successful.36 As for the congregation itself, membership rose to 90 families in 1935, and the estimated Jewish population of Sumter exceeded 200.37 Jews from smaller surrounding towns such as Bishopville, Denmark, Greeleyville, Hartsville, Kingstree, Manning, Mayesville, and Summerton came to Temple Sinai for services and were active members.38 Membership throughout the mid-to-late 20th century fluctuated between 70 and 90 families, and it did not fall below 60 until the mid-1980s.39

Conservative Practices Introduced

Samuel R. Shillman, from Chattanooga, TN, served as Temple Sinai’s rabbi from1930 until 1948.40 In 1942, Rabbi Shillman encouraged congregation Sinai to attend the cornerstone-laying ceremony for a new synagogue in neighboring Dillon. Shillman was integral in helping Dillon organize their own congregation just three years prior in 1939. During those three years, Shillman would travel to Dillon once a month for services at Ohav Shalom.41

After Rabbi Shillman left, Rabbi J. Aaron Levy succeeded him in 1949.42 Rabbi Levy began introducing Conservative practices to the Reform congregation. Their first bar mitzvah at the congregation was held in 1964.43 Levy also served congregations in the neighboring small towns such as Camden and Darlington.44

In the 1960s, the Jewish population of Sumter reached its peak: 390 individuals.45 Congregation Sinai relied on a student rabbi from the Hebrew Union College in the late 60s and early 70s, Edward Ruttenberg.46 He also continued to introduce traditional practices to the congregation. For example, he always wore a yarmulke and used more Hebrew in his services than members were accustomed to.47 Because of this, he suggested that Hebrew should be taught to students in the Sunday school, arguing that Hebrew united all Jews.48 The school board did not introduce Hebrew into the Sunday school curriculum until 1976.49

Rabbi Avshalom Magidovitch began at Temple Sinai in 1973, and brought to the congregation even more Conservative rituals, oneg Shabbat reception, and adult educational classes.50 He served the congregation until his death in 1979.51

Decline in Religious Life

Besides High Holy Day services, which tended to draw larger crowds, the congregation held community Seders and the Sunday school hosted annual Chanukah and Purim parties.52 The Men’s Club organized collections for the Jewish Welfare Fund. They were able to donate thousands of dollars to the United Jewish Appeal, as well as several other Jewish charities.53 The women of Temple Sinai’s Sisterhood, originally the Ladies Aid Society, also organized fundraising events. They held annual bulb sales and garage sales to raise funds for any repairs or renovations the synagogue needed.54 They hosted oneg Shabbat services and provided light refreshments after services. They also served meals at the annual meetings, threw holiday parties, decorated the sanctuary, supervised the upkeep of the synagogue, and briefly financially supported Temple Sinai’s choir.55

By 1980, the Jewish population in Sumter had decreased to around 190 individuals.56 Congregation Sinai hired Milton Schlager as their rabbi and he began appealing to the younger Jewish couples of Sumter, which resulted in higher attendance.57 He tried to introduce new rituals to his services and varied his sermons. Despite his efforts, however, the board decided not to renew his contract by the end of the decade.58 By 1989, the Sunday school had become inactive and the Jewish children of Sumter had to travel to Columbia or Florence for religious school.59

In 1991, the congregation hired Rabbi Richard Leviton, even though the congregation only had 60 members, and Rabbi Schlager’s contract had been terminated because so few attended Friday services.60 The Sunday school was able to continue operation with just six young children while older children continued to attend Columbia’s Tree of Life Sunday school.61 Rabbi Leviton left Congregation Sinai in 1996 when his contract ended, though the congregation was unable to afford a full-time rabbi anyway. Until the turn of the century, Temple Sinai relied on student rabbis from Hebrew Union College.62

Congregation Sinai Today

Today, Temple Sinai has a low attendance rate of mostly older congregation members, with a part-time rabbi or lay reader leading services.63 On average, about 15 people attend services.65 Currently, there is no Sunday school and the few children that are within the congregation travel to Columbia for religious education.66 The Sisterhood, however, is still active and serves as the “backbone” of the congregation.67

In order to preserve their history, the congregation donated its archives to the Jewish Heritage Collection at the College of Charleston in 2007.69 Since the 2018 opening of the Temple Sinai Jewish History museum, the temple continues to serve as the heart of Jewish life in Sumter, SC.

Architectural Description:

In 1999, Temple Sinai was nominated and listed on the National Register of Historic Places for its significant architecture, as well as the congregation’s historical and religious significance.70 The NRHP nomination describes Temple Sinai as:

“a two-story brick building with Moorish Revival detailing constructed in 1912-13. Its central entrance is flanked by castellated towers featuring domed roofs. The shallow entry portico is supported by cast stone Moorish octagonal columns, surmounted by cast stone spheres. The synagogue is adorned by ten Moorish stained glass windows. A circular stained glass window pierces the wall above the central entry portico. The cornice of the building features brick stringcourses. The synagogue has a flat roof with a metal clad dome containing a lantern at its peak. The Barnett Memorial Addition, a two-story brick auditorium addition built in 1932, is adjacent to the rear of the synagogue and also features Moorish detailing in the doors and windows and repeats the brick stringcourse around the cornice. The Hyman Brody Building, a one-story brick addition on the south of the auditorium wing built in 1956, is used for Sabbath school classes and offices. The building is in a good state of repair and is an important landmark in the city of Sumter.

Temple Sinai rests on a brick foundation clad in stucco. The original portion of the building-the sanctuary section-is a two-story brick building constructed in 1912-13. Though this high-style building was almost certainly designed by an architect, no known documentation substantiating this supposition has been discovered. The building committee responsible for the construction of the original sanctuary in 1912-13 was Isaac Schwartz, H.D. Barnett, and Julian H. Levy. This building replaced an earlier wooden temple probably constructed in the 1890s.

The interior of the sanctuary features plastered walls which rise two stories to the domed ceiling. The ten stained glass windows in the sanctuary are believed to have been made in Germany in 1912. The upper, or circular portions of the windows feature Old Testament symbols and the lower, or rectangular, windows depict Old Testament stories. The sanctuary also contains an organ bought from Henry Pilcher’s Sons, of Louisville, Kentucky, in 1920; the organ was restored in 1982 in memory of Shirley Ness Housen. The Ark of the Covenant in the sanctuary was rebuilt in 1967-68 by architects Upshur, Riley, and Bultman as the gift of the Reuben Brody family, members of Temple Sinai. The raised pulpit features a carved wooden lectern, two large menorahs, and four cushioned wooden chairs. The pews contain scrolled arm rests and paneled supports.

The two-story brick auditorium addition, built in 1932, was designed to repeat the architectural features of the 1912-13 sanctuary. Its facade faces north on West Hampton Avenue, and it features a recessed section with a central door, approached by a double set of brick steps ascending to a central landing. The door is constructed with an applied panel of Moorish motif and is topped by an elliptical stained glass transom. Above the door on the second floor are two small Moorish stained glass windows. To the left of the doorway is a full length two-story stained glass window which is the same size as those in the sanctuary. The stringcourses at the cornice of the temple are continued around the cornice of the addition. The building also contains a large auditorium/banquet hall on the first floor. The second floor contains classrooms and offices. The other facades of the addition have two-over-two sash windows. Access to the auditorium was originally by a door on the western elevation, one which was flanked by windows. When the 1956 addition was constructed a hallway was extended to the auditorium. A new door was installed several feet in front of the original door. A second floor door on the southern elevation of the addition provides fire escape access. The addition has a flat roof.

In 1956, the Hyman Brody Building was attached to the southern end of the 1932 addition. This building provided additional school rooms, restrooms, and office space for the synagogue. It is a one-story brick building resting on concrete footings. It has a flat roof and is very simple in design, yet carries the Moorish motif in the brick surround to the recessed entry porch on the building’s western elevation. The 1956 addition has a central door flanked by sets of casement windows. Casement windows pierce the other elevations of the building as well. This addition extends on the southern side of the 1932 addition from a few feet from the sidewalk to the rear of the 1932 addition, where a kitchen in the 1956 addition abuts the auditorium/banquet hall.

The temple stands at the corner of Church Street and West Hampton Avenue in downtown Sumter. It helps to anchor one end of the local historic district known as the Hampton Park Historic District, a ca. 1870-ca. 1915 residential neighborhood of primarily Victorian and Craftsman/bungalow-style houses. The land upon which Temple Sinai stands was originally a single lot on the corner of Church Street and West Hampton Avenue and subsequently grew to encompass four lots on the corner, allowing for expansion and parking.”71

In June of 2018, Temple Sinai opened the Temple Sinai Jewish History Center in a partnership with the Sumter County Museum.72 While the sanctuary is used for Shabbat and High Holiday services, the social hall houses the permanent exhibit.73 The exhibit features information on Jewish history in Sumter and South Carolina, as well as a section on the Holocaust and Sumter’s personal ties.74

MST #848: Temple Sinai, Sumter SC

Temple Sinai is home to Holocaust Memorial Scroll MST #848. After their invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1939, the Nazi authorities began to persecute Jews living in this occupied territory. Nazi authorities stripped Czechoslovak Jews of their rights, property, and businesses. In 1942, the regime ordered congregations throughout the Czech regions of Bohemia and Moravia to send any religious objects to the Jewish Museum of Prague, located within the Pinkas Synagogue. Over 1,800 Torah scrolls survived the war in this location. The Memorial Scrolls Trust, headquartered in London, took over their care after the war. This organization painstakingly restored and distributed these Torah scrolls to synagogues around the world. Sumter’s Torah was among those recovered by the Trust and has been traced to the village of Mladá Vožice, Czechia.

Mladá Vožice is a small town located in the Southern Bohemia, Czechia. The town’s earliest known Jewish community can be traced to 1701, peaking in 1880 with 152 members—the same year MST #848 was written. Though we know this community did not survive the Holocaust, the exact fate of all its members is not known. After correspondence between Memorial Scrolls Trust and Temple Sinai, MST #848 reached South Carolina in 1972 and was dedicated in memory of the late Rabbi J. Aaron Levy on January 12, 1973. Other devotional objects are also dedicated to further members of the Sumter Jewish community.

Endnotes

1-4. “ISJL – South Carolina Sumter Encyclopedia.” 2021. Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life. 2021.

5. “ISJL – South Carolina Sumter Temple Sinai Encyclopedia.” 2021. Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life. 2021.

6. ibid.

7. “ISJL – South Carolina Sumter Encyclopedia.” 2021. Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life. 2021.

8-12. “ISJL – South Carolina Sumter Temple Sinai Encyclopedia.” 2021. Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life. 2021.

13. “ISJL – South Carolina Sumter Encyclopedia.” 2021. Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life. 2021.; “ISJL – South Carolina Sumter Temple Sinai Encyclopedia.” 2021. Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life. 2021.

14. “ISJL – South Carolina Sumter Temple Sinai Encyclopedia.” 2021. Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life. 2021.

15-20. “ISJL – South Carolina Sumter Encyclopedia.” 2021. Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life. 2021.

21. Ferris, Marcie Cohen. Matzoh Ball Gumbo: Culinary Tales of the Jewish South. Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press. Accessed October 19, 2021.

22-27. “ISJL – South Carolina Sumter Temple Sinai Encyclopedia.” 2021. Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life. 2021.

28. “ISJL – South Carolina Sumter Encyclopedia.” 2021. Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life. 2021.

29-44. “ISJL – South Carolina Sumter Temple Sinai Encyclopedia.” 2021. Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life. 2021.

45. “ISJL – South Carolina Sumter Encyclopedia.” 2021. Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life. 2021.

46-55. “ISJL – South Carolina Sumter Temple Sinai Encyclopedia.” 2021. Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life. 2021.

56. “ISJL – South Carolina Sumter Encyclopedia.” 2021. Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life. 2021.

57-68. “ISJL – South Carolina Sumter Temple Sinai Encyclopedia.” 2021. Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life. 2021.

69. “ISJL – South Carolina Sumter Encyclopedia.” 2021. Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life. 2021.

70. “SC Historic Properties Record : National Register Listing : Temple Sinai [S10817743026].” 2015. Sc.gov. 2015. http://schpr.sc.gov/index.php/Detail/properties/13021.

71. ibid.

72-74. “Temple Sinai in Sumter South Carolina.” 2018. Sumtercountymuseum.org. 2018. https://sumtercountymuseum.org/templesinai/.